Introduction to water pollution

Last updated: May 10, 2012.

Next time you pour yourself a cool, clear glass of

water, hold it up to the light and look very closely.

Do you see any pollution? Any spilled oil? Stray bacteria? Toxic chemicals? Bug-eyed

microscopic creatures?

Probably not—and nor are you likely to. We

assume the water we put inside ourselves is as clean as clean can be,

and mostly it is. But think about things logically, and you might

start having doubts. We know that water pollution exists (often in

quite large quantities) and we also know that the world's water is

constantly recycling itself. So how can we be sure that the water we

drink is perfectly clean and healthy?

The answer is that water companies go to great lengths to purify drinking water, whether it

comes from a bottle or a tap (faucet). That's very reassuring, but

what does it tell us about the rest of the water on our planet: the

water we swim or bathe in, the water in our rivers, and the water in

our seas? Would you be happy to drink water from your local river?

Would it bother you if you accidentally swallowed water from the sea?

Do you worry about the water that comes out of your tap and drink

bottled water instead? The fact that we all do

worry about things like this is a sign that water pollution is one of the world's

biggest environmental problems. What causes it, what effect does it

have, and what can we do to stop it?

What is water pollution?

Close your eyes a moment and say the words "water

pollution." What images come into your mind?

Photo: US National Park Service, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, courtesy of US EPA Great Lakes National Program office.

Maybe oil tanker spills in the ocean or plastic trash washed up on the beach? Maybe

you've seen shopping carts floating in your local river or huge

growths of algae turning lakes green? These are all examples of water

pollution, but they're by no means the only examples. That's why, if

we want to define "water pollution," we have to use quite a wide

and general definition. Usually what we mean by pollution is

"something that doesn't belong in the natural environment."

An oil spill in the ocean or a sewage spill in a

river meet this definition of pollution, but other types of pollution

are different. What if you dragged a net through San Francisco bay

and hauled up a load of

Asian kelp?

What if you went fishing in England and caught an

American signal crayfish? You might be delighted to have caught something more than an old boot, but both

these things are examples of pollution: they are what we call

invasive species (or "alien species") that don't belong in the places

where we now commonly find them.

So anything that doesn't belong where we find it

is pollution, right? Not exactly. Suppose you find one molecule of

oil in the Pacific ocean. Would you consider that pollution? How

about two molecules? How about a cup of oil... or a gallon.... or 10

barrels... or.... ? At what point does something fairly harmless

become a problem? At what point does an ordinary substance become

pollution?

Clearly, we have to modify our definition a little

bit so it takes account of the factors we've just considered. Let's

define water pollution like this:

Water pollution is a chemical or

biological substance that builds up in the environment enough to be

toxic, harmful, or a nuisance to humans, other animals, or other

living things.

What causes water pollution?

That sounds like a simple question, but it's much

harder to answer than you might think. To start with, each of the

different types of water pollution has a different cause. So, for

example, it's relatively common for the world's rivers and seas to be

polluted by human sewage and wastewater. But what causes the

pollution? It's not simply that humans and animals produce sewage;

it's that sewage is often flushed untreated into the water. Even in

relatively wealthy countries such as the United States and the United

Kingdom, vast amounts of sewage routinely find their way into coastal

waters where people bathe and from which fish and shellfish are

caught. [1,2]

But why is the sewage flushed into the seas

instead of being pumped through a treatment plant to remove toxic

chemicals and bacteria? Is it a matter of economics (people don't

want to pay more for their water)? Is it a matter of law and regulation (water

companies are not fined enough when they pollute)? Is it that people

don't care enough to protect the environment we all depend on? Or is

it that we don't appreciate the problem of pollution—or perhaps that

we have too many other things to worry about? You could argue that

sewage and wastewater pollution is caused by any (or all) of these

things.

What causes people to throw trash by the side of a highway?

Photo courtesy of US Fish & Wildlife Service Digital Library.

The same goes for pretty much all the other types

of water pollution. You might believe that careless oil companies are

responsible when oil tankers or oil rigs leak oil into the oceans.

Then again, you might consider how very upset people become when the

price of petrol (gasoline) increases. If we forced all the oil

companies to build stronger and more robust tankers, and to adopt

much more stringent safety procedures on their oil rigs so accidents

and leaks were less likely, how much more would we all have to pay to

fill up our cars? How much would the price of everyday goods (which

have to factor in a certain amount for transportation) have to rise

to pay for it? Maybe a lot, maybe not much at all, but we do

at least have to ask the question. As before, you could argue that greedy oil companies

cause water pollution—or you could probe further and ask whether

society as a whole has come to value cheap gasoline over pristine

oceans. Are we all partly to blame?

Whichever form of water pollution you consider,

you'll find the simple causes lead to deeper questions about how our

society works. Take the problem of acid rain, for example. That's

caused when air pollution from smokestacks blows long distances

before meeting up with rain clouds. When the rain falls, it dissolves

the pollution and produces acid, which changes the pH (acid-alkali balance) of

lakes and rivers, making them too acidic to support fish life. Who or

what is responsible for acid rain? Is it the companies who operate

the smokestacks? Since many of them are power plants, is it the

ordinary people—you and me—who use their electricity? Is it the

governments who fail to do anything about the problem?

Once we start to think in this way, and look at

the deeper, less obvious causes, it starts to make sense why

pollution is such a widespread problem and such a hard thing to

solve.

What effect does water pollution have?

Water pollution is often really horrible to look

at: no-one likes to see plastic bottles strewn across their favorite

beach or plastic bags littering a river. But often the effects are

more drastic and much more disturbing: think of dead fish floating on

a polluted lake or oil-caked birds flapping hopelessly on a beach

inland from a tanker spill.

We've defined water pollution as something "toxic,

harmful, or a nuisance," but how bad can its effects be? The answer

is all about concentration: how much of a polluting substance or

chemical is present in a river, lake, or sea. If there's enough oil

to wipe out one or more species, an entire ecosystem may be affected,

because each species depends critically on all the others. You might

think it doesn't matter if all the insects (say) disappeared from a

river corridor. But what feeds on those insects? Bats, birds, and

other creatures. And what feeds on those? A relatively small change

to one part of an ecosystem can cause knock-on damage felt by many

other species. Effects like that can take years to fully manifest

themselves, which means they're not always obvious and not always

easy to trace back to a single episode of pollution.

Although many people care passionately about the

environment, humans are ultimately programmed to be selfish

creatures: we care most about our own survival. When we see oil

tanker spills on the TV, we get angry and upset—but if we're part of

a community that's affected by a spill like that, we care very much

more. It's difficult to put a value on a clean river, because it

benefits many different communities in many different ways [10];

quantifying the effects of river pollution is therefore very

difficult. It's easier to see the effects of localized pollution on

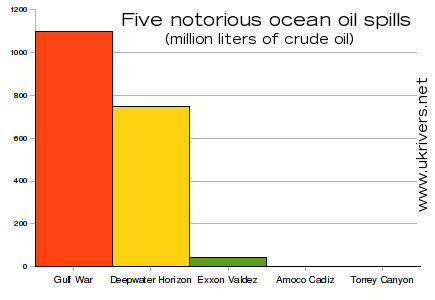

something like a coastal community. The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill

saw at least 42 million liters (11 million gallons) of crude oil discharged

into Prince William Sound in Alaska and decimated the local

community. [11] Similar devastation was reported in the Gulf of Mexico

after a huge oil leak from BP's Deepwater Horizon drilling platform in 2010. [12]

What effect will this spilled oil have when it runs into the ground?

Could it damage someone's health years or even decades in the future?

Photo courtesy of US Fish & Wildlife Service Digital Library.

Just as we need to think hard about the causes of

pollution—looking beyond the immediate reasons for deeper social or

economic factors that may have caused them—so we need to take care

when we think about pollution's effects. It's relatively easy to

consider something like an oil tanker spill and measure the effect on

a local fishing community over the coming days, weeks, months, and

years. But what about the longer-term effects of pollution happening

in many places at once? Although some water pollution can be neatly

traced to a single place, time, or event (we call it point-source

pollution), much of it builds up from many different sources over

a long period of time (we call that nonpoint-source pollution

or diffuse pollution).

What are the effects of, for example, all the chemical factories in

the world that dump toxic liquids into wastewater? How much of that

finds its way into rivers, seas, and even groundwater that we might

drink? Are the concentrations of toxics too small to worry about? And

how do we know? One problem we have is that toxic chemicals may be

carcinogenic (cancer-causing), but cancers take years or decades to

develop and people get them for many different reasons, so it can be

very hard to say, with any certainty, that particular factories have

a harmful effect on human health because they contribute to water

pollution. [13]

As with many other environmental problems, water

pollution is hard to tackle because its effects (which may be

long-term and subtle) are often hard to trace to a particular cause.

If we know an oil tanker has broken up near the coast, we can

instantly identify that as a potential source of water pollution and

take immediate action to reduce any effect it may have. But we can

look at a dirty river, devoid of fish and other life, running

through a city, and find it hard to know who or what to blame. And if

we can't easily identify the cause of the problem, coming up with a

solution can be almost impossible.

What's the solution to water pollution?

You might think water pollution would be an easy

problem to solve, but it's not. I've taken pains to point out that

the causes and effects of water pollution are more subtle than they

might, at first, appear. By recognizing the complexity of the

problem, we stand a better chance of solving it.

The first thing we need to note is that water

pollution is not a single problem but many different ones. Although

lots of different things can lead to a river or sea being heavily

polluted, it can be very helpful to see them as separate problems and

try to find specific solutions in each case.

Suppose we consider the hypothetical city of

Nowheresville, with the appallingly polluted Nowhere River running

through it. The pollution could be a combination of sewage, oil, acid rain,

highway runoff, and all kinds of other things. What can we do about

it?

- Sewage pollution in rivers is often be caused by sewage treatment

plants overflowing through CSOs (combined sewage overflows) at times of very heavy rainfall; excess wastewater

is deliberately allowed to "overflow" into rivers and seas because the alternative

would be for sewage to back up into people's homes—or so the water

companies argue. The solution there has to be investment in better

treatment plants that don't have those kinds of overflows, which

would mean greater investment and possibly higher water bills. Maybe

we'd need tougher pollution laws or regulation of water companies to

make that actually happen, which would in turn need greater public

awareness and political pressure.

- The oil in the river might be easier to tackle. Maybe that's a matter of running a public education campaign so local

people don't tip discarded engine oil down drains, but take it to proper disposal facilities in garages and

recycling centers instead.

- Acid rain is at the opposite end of the scale: it

might be generated by power plants in an entirely different

country or continent—and companies over whom we have absolutely no control. But,

again, public awareness can make a difference. In the 1980s, the

Norwegian environment minister caused an international diplomatic

scandal when he publicly referred to his British counterpart as a

"drittsekk" (dirtbag) because he was making too little effort to stop British power plants depositing

acid rain on Norway. But this one word, "drittsekk," did a great deal to raise awareness of

acid rain in Britain, which many people had never even considered before. [14]

- Highway runoff is another difficult problem to

tackle because there are so many roads and so many cars. But, thanks

to growing public awareness of the problem, newer highways are built

to much higher standards than older ones. Where highways run close to

rivers and other watercourses, it's much more common to have

pollution traps, often with reedbeds planted around them, to capture

and remove pollutants.

We can let water pollution defeat and deflate us,

or we can break the seemingly huge problem into a number of smaller,

more manageable problems and go after smaller, highly targeted

solutions; eventually, all these things will make a noticeable

difference to the quality of our water. It may take years or decades,

but we can and will turn things around. We can make a difference; we can beat water pollution!

Written by Chris Woodford for the UK Rivers Network. © Copyright Chris Woodford 2012.

Find out more

On the web

Books

Introductory

- Allaby, Michael. Water: Its Global Nature. New York: Facts on File, 1992. [Excellent,

simple introduction to global importance of water.]

- Day, Trevor. Oceans. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1999. [Excellent overview of all aspects of oceans.]

- Living Earth Foundations. The Oceans: A Celebration. London: Ebury Press, 1993.

- Ross, David. Introduction to Oceanography. New York: HarperCollins, 1995. [Ch 16 "Marine Pollution" is a very good introduction and overview.]

- Stowe, Keith. Exploring Ocean Science. New York: Wiley, 1996. [See Part 9 "The Health of the Oceans".]

- Thurman, Harold and Alan Trujillo. Essentials of Oceanography. Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1999. [Good coverage of marine pollution in Ch11 "The Coastal Ocean".]

Detailed general books on water pollution

- Farmer, Andrew. Managing Environmental Pollution. London/New York: Routledge, 1997. [Good

chapter on marine pollution.]

- GESAMP (Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Pollution). The State of the Marine Environment. Oxford/New York: Blackwell, 1990. [Definitive survey]

- Wood, I.R., R.G. Bell, and D.L. Wilkinson. Ocean Disposal of Wastewater. Singapore: World

Science, 1993.

Chemical and biological effects of water pollution

- Alloway, B.J. and D.C. Ayres. Chemical Principles of Environmental Pollution. London/New York: Blackie/Chapman and Hall, 1997. [Good on chemical and toxiological effects of pollutants]

- Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 1962. [Classic introduction to the threat posed by use of chemicals (mainly pesticides) on the natural environment.]

- Dudley, Nigel. Nitrates: The Threat to Food and Water. London: Green Point, 1990. [Simple, accessible guide to nitrate pollution from agriculture etc. and what to do about it.]

- Sindermann, Carl. Ocean Pollution: Effects on Living Resources and Humans. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1996.

- Steingraber, Sandra. Living Downstream: An ecologist looks at cancer and the environment, Virago, 1999/2010.

[Silent Spring revisited. A combination of powerful scientific evidence to support links between environmental pollution and different kinds of

cancer and moving, poetic reflections on Steingraber's own battles against cancer.]

- Tapp, J., J. Wharfe, and S. Hunt. Toxic Impacts of Waste on the Aquatic Environment. London: Royal Society of Chemistry, 1996.

- Welch, E.B. and T. Lindell. Ecological Effects of Wastewater: Applied Limnology and Pollutant Effects.

London: E & F N Spon, 1992.

Political and economic analysis

- Cook, Hadrian F. The Protection and Conservation of Water Resources: A British Perspective. Chichester/New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

- Man and the Maritime Environment. Edited by Stephen Fisher. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1994.

- Gourlay, K.A. Poisoners of the Seas, London; Zed Books, 1980.

- Gourlay, K.A. World of Waste, London; Zed Books, 1992.

- Harrison, Paul. The Third Revolution: Population, Environment, and a Sustainable World., New York/London: Penguin Books. [See Ch14: "Sea of troubles: Polluted waters".]

- Independent World Commission on the Oceans. The Oceans: Our Future. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Wilder, Robert Jay. Listening to the Sea: The Politics of Environmental Protection. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1998. [Political analysis of the problems of protecting the oceans]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future. London/New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. [See Ch10 "Managing the Commons", Section 1. "Oceans: The Balance of Life".

Articles

- Borgese, Elisabeth. "The Law of the Sea." Scientific American, March 1983, Volume 248 Number 3, p. 28. [Introduction to the Convention on the Law of the Sea and the problems of signing international agreements to protect the world's oceans.]

- Clark, W.C. "Managing Planet Earth." Scientific American, September 1989, Volume 261 Number 3, p. 48.

- Costanza, Robert, et al. "Principles for Sustainable Governance of the Oceans." Science, Volume 281, Number 5374

Issue of 10 Jul 1998, pp. 198-199

- Deere-Jones, Tim. "Back to the Land: The Sea-to-Land Transfer of Radioactive Pollution." The

Ecologist, Vol 21 No 1, January/February 1991, p.18. [Considers effects of nuclear pollution, notably discharges from Sellafield in the

Irish Sea, and their political background.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. "Ocean Pollution Seen from Rafts." Statement to US Senate Committee on Oceans and Atmosphere, November 8, 1971. In Oceanography: Contemporary Readings in Ocean Science, Ed. R. Gordon Pirie. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

- la Riviere, J.W. Maurits. "Threats to the World's Water." Scientific American, September 1989, p.48. [A general introduction to global water water resources and the threats they face.]

- Macdonald, Ian. "Natural Oil Spills." Scientific American, November 1998. As much oil seeps into the Gulf of Mexico every decade from natural fissures in the seabed as was lost from the Exxon Valdez.

- Mitchell, John. "In the wake of the spill: ten years after the Exxon Valdez." National Geographic,March 1999.

- Ryan, Heather E. "[E] Conversations: Sandra Steingraber: Living Downstream and Fighting Back", E Magazine, Nov-Dec 1999.

- Nadis, Stephen. "The Sub-Seabed Solution", Atlantic Monthly, October 1996: "Far from being embraced, a promising solution to the radioactive-waste problem faces stiff opposition from the federal government, the nuclear industry, and environmental

interests". Unfortunately, you now need a subscription to Atlantic Monthly to read this.

- Schneider, David. "Not in my back yard", Scientific American, Volume 276 Number 3, 1997, p. 20. A scientific look at using the deep ocean floor as a nuclear waste repository.

- Down the Drain, Scientific American, December 1996. How Russian nuclear waste if disposed of in alarming ways.

- Wood, Campbell "[E] Conversations: Ted Danson: Acting for Oceans", E Magazine, Jan-Feb 1998

- Scientific American: Feature Article: Enriching the Sea to Death: August 1998

- Scientific American: Explore!: Costly Interlopers: February 15, 1999 [this article has

now been removed from Sci Am's website, but see if you can track it down somehow]

References

- According to NRDC, over 700 US communities have CSOs (combined sewer overflows) that can discharge raw sewage and runoff into waterways during high rainfall. See NRDC: Testing the Waters, 2011.

- In the UK, there are an estimated 20,000 CSOs, of which 500 flow directly onto or near beaches. See

Britain's Dirty Beaches, BBC News, 7 September 2009.

- British environmental group Surfers Against Sewage was set up in the early 1990s to fight this problem.

- A 1994 leaflet by the US EPA reported: "200 million gallons of used motor oil are improperly disposed of... one gallon of used oil [can]... contaminate up to one million gallons of drinking water." See EPA Collecting used Oil for Recycling/Reuse [PDF].

- A 1999 report by David Pimentel et al estimated the cost of invasive species to the US at $138 billion.

See Environmental and economic costs associated with non-indigenous species in the United States, Cornell University Press Release, June 12, 1999.

- According to NRDC: "In 2010, polluted runoff and stormwater caused or contributed to 8,712 closing/advisory days at coastal and Great Lakes beaches, making it the largest known source of contamination problems." See NRDC: Testing the Waters, 2011.

- See Marine Conservation Society: The Problem with Plastics, 2011.

- For more about how oil gets into the oceans, see Accidental discharges of oil. For an example of how oil affects sensitive marine areas, see Shipping and Oil Spills, Australian Government: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, March 2006 [PDF].

- Notably International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), originally adopted in 1973 and revised several times since then. On the effectiveness of MARPOL, see

The Marpol Convention (Good Planet, 200) and Has MARPOL reduced intentional oil discharges by Ronald B. Mitchell (1994).

- In May 2012, US community alliance Protect the Flows estimated that the Colorado River brought recreational benefits of $17 billion. See Study: Colorado River generating money and jobs

- For lasting ecosystem damage, see What we learned from the Exxon Valdez by Stephen Dowling, BBC News, 26 March 2009.

For the effect on the local community, see Exxon Valdez oil disaster still affects communities, wildlife Sydney Morning Herald, May 4, 2010.

- Gulf spill's effects 'may not be seen for a decade' By Jason Palmer, BBC News, 21 February 2011.

- Sandra Steingraber's Living Downstream: An Ecologist's Personal Investigation of Cancer and the Environment is a classic account of attempts to trace human health problems to environmental pollution.

- The "drittsekk" incident is briefly recounted in Gummer goes on getting greener by Geoffrey Lean, Telegraph, 31 December 2009.