Adopting a river: How to get out, get dirty, and make a difference!

Last updated: 23 December 2007.

Introduction:

Why adopt a river?

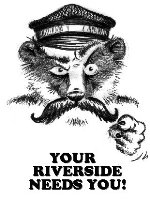

Major Badger:

Picture by "V"

Major Badger:

Picture by "V"

If

news reports are anything to go by, our rivers have never been in

better shape. Even so, many rivers are plagued by all kinds of

problems, from discarded shopping trolleys to invasive species, from

new quarries and roads to neglect and decay, and from very localized

agricultural pollution or occasional sewage spills to the massive

looming threat from climate change.

All

round the country, there are dozens of groups and thousands of

individuals who give up some of their spare time to help protect

their local rivers. The UK Rivers Network was set up in 1999 to help

these groups share their ideas and work together more effectively.

It's far from a comprehensive network and most rivers have no local

groups looking out for them. That's a position we're very keen to

change.

Every

so often, people write to us explaining a particular problem with

their local river and asking what they can do about it. More often

than not, it's a pollution problem; sometimes it's a threat to a

river from a new development of some kind – a quarry, perhaps,

or a bypass that would destroy part of a floodplain. All these

situations are different and it's difficult for us to offer general

advice. Generally, though, the answer is always the same: what you

can do to make a difference is adopt your river:

you can make it the focus of a community cleanup or restoration

project, campaign, or celebration.

One

thing is always true about protecting the environment: although laws,

policies, and government agencies have a crucial role to play,

ultimately much comes down to what ordinary people can do to tackle

local problems themselves. If you're unhappy about shopping trolleys

in your river, you could write a “Why-oh-why” letter to

your local paper moaning about your local council, or the problem of

disaffected teenagers, or your bitterness about people who don't

care. Or you could make a stand, make a difference, and try to do

something about it. You could start a local campaign to clean up the

river: you could get the local community involved not just in rubbish

collection but in long-term habitat restoration and even in holding

an annual celebration of the river. Which would you rather do? Moan

about the negative—or do something positive? Adopting a river

can be hard work, but it can be rewarding for the environment and

empowering for the local community. Earth's environmental problems

are far from trivial, but you can do things that make a difference.

And you can start right now!

This booklet is not written for

river experts: it's written for ordinary people who want to make a

difference to their local rivers—people who may become

inadvertent river experts in due course! We've kept river and

environmental terminology to a minimum. It's designed to work

equally well as a Web page and if you print it out (that's why all the

web links are spelled out in full.

This booklet is a work in

progress—and it is intended always to be that way. We hope people will

keep feeding us thoughts and ideas so we can constantly extend and

expand it. Tell us what you think: Is this a useful guide? Is it a load

of rubbish? What can we improve? In particular, we need your help

developing some useful

“Adopt-a-river” case studies.

How to adopt a river

1.What does “adopting a river” actually mean?

No-one owns our rivers. Even so, many people have so-called

“riparian

rights” to the rivers that run through or near their

land. In short, they own the riverbed, but not the water that runs over

it. They also have the right to receive the water flowing from upstream

in its natural state (undiminished in quality or quantity). Some of our

rivers are important ecologically and carry various levels of

protection; a few are designated as Sites of Special Scientific

Interest (SSSI), for example, while many are home to strictly

protected species such as otters. When we talk about “adopting

a river” in this booklet, we mean taking on the notional role

of guardian for a particular stretch of river near you. Generally,

you will need to do that with the full cooperation of the people who

own the riparian rights and you will need to be very sensitive to the

importance of the environment you are trying to protect. Having said

that, if you've reached a point where you are considering adopting a

river, usually something is not right: a river is typically being

neglected, abused, or threatened. Your mission is to do something

about that. Adopting a river can bring you into conflict with

riparian owners, farmers, local councils, and other bodies whom you

believe (rightly or wrongly) are neglecting their responsibilities.

In practice, adopting a river can be as much about crafty

campaigning, local politics, media management, and public relations

as about doing physical things to make the river better. But don't

let that put you off!

2.

What are your objectives?

People

talk a lot about “saving the environment”, “protecting

the planet”, and “helping the Earth”, but such

vague generalities are not much help when it comes to adopting a

river. It's important to have a clear idea of your objectives when

you start.

If

you're fighting a development, such as a landfill site or quarry that

would devastate part of the river's ecosystem, your objective might

seem clear: what you want to do is stop the development and save the

river. But is that really the end of your work? You might start to

consider why your local council, regional development agency, or

national government has put policies in place that led to a direct

threat to your river... and you might work to change those policies

later on. Otherwise, the threat to your river could reappear in a few

years time or in someone else's backyard. Needless to say, if you

play this game too readily, you can soon find yourself bogged down in

complexity: you can start off wondering why your house floods every

few years... and find yourself waving banners at a climate conference

in the Hague! Environmentalists have a saying, “Think global,

act local”, which means do something positive and effective in

your own life without losing sight of the bigger picture. Really that

saying should be “Think global, act local, think global.”

There's no point in piling up the sand-bags outside your front door

if you don't give at least some thought to the looming threat from

climate change and how the world, as a whole, should be addressing

it.

Small

is beautiful

It's

usually best to start off with small, achieveable goals—however

small they might be. You can always set yourself bigger, more

ambitious goals later. But if you start off with goals that are too

ambitious and don't achieve them, that will be very disempowering and

will probably destroy your enthusiasm for the project. It is usually

better to spend a day hauling shopping trolleys out of a river or

picking litter up off the riverbanks than to spend a year in endless

meetings with local councils and have little or nothing to show for

your efforts.

Later

on, if our project is a success, you might want to turn your river

project into a more sustainable organization, such as a charity.

Setting up a charity can be quite a complex and formal process and it

does require you to specify your aims very clearly. For the time

being, less clearly defined aims are fine!

3.

Cooperation or conflict?

Another

pitfall is having a number of conflicting aims. One difficulty that

river groups often come across is the potential conflict between

people who have different visions of our riverside world. There may

well be differences of opinion between landowers who want to keep

parts of their estate private and those who believe in greater public

access and the right to roam; between local councils who (as they see

it) are trying to allow new homes to revitalize the economy and

environmentalists who would prefer no new development on greenfield

land; or between fishermen and country-sports enthusiasts, on the one

hand, and people who believe such things are morally wrong, on the

other. Generally speaking, community groups and projects work best

when they are as inclusive as possible:

seek the common ground

if you possibly can; try to involve as many different people in your

group or project as you possibly can. As a general rule, cooperation

is the best way to go.

Having

said that, the world is dominated by economic interests and

environmental protection often ranks as little more than an

afterthought. Local councils may well be working for the good of the

community, but some, demonstrably, also work hand-in-hand with

property developers. National government policies may also be

socially motivated—but they too are just as susceptible to

special pleading and vested interests. Inevitably, there are times

when cooperation gets you nowhere. The meek may well inherit the

Earth, but it'll be an Earth covered with motorways, housing

developments, landfills, and quarries. There are times when you have

no choice but to take a confrontational stance, however reluctantly.

If

your local river is a mess and you want to do something about it, a

confrontational, finger-pointing campaign, perhaps waged with the

help of your local newspaper, can work wonders. But don't be

confrontational for the sake of it. Use confrontation to win over

your opponents. Get the bad guys on your side. Make them see the

error of their ways and clean up their act. Use confrontation

to make them cooperate in the broader

interests of your

community.

4.

Who are the players?

There's

nothing to stop you adopting a river all by yourself—but you

will generally get on much better if you work with other people. One

of the first things you need to do is contact other local groups and

organizations and see how they can help you. Your shopping list of

groups to contact should look like this:

- Local branch of the Environment

Agency (look under “Environment Agency” in your local phone book, call

their general enquiry line on 0645-333111, or see http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/).

- The environment department of your local town, district, or

county council.

- The parish councils for villages or communities through which

your river runs.

- Any local angling groups you know about. If you're not sure

whether there are any, ask at your local

library. Don't forget to sound out the person who runs the local

fishing shop!

- Any river protection groups already active in your area, on the

same river upstream or downstream, or on

different rivers nearby. (For a list of active UK river groups, see our

network page.)

- Any more general environmental

groups in the area. Just about every county in Britain has an active

branch of the Wildlife Trusts (see http://www.wildlifetrusts.org)

and many of these have highly experienced river or wetland project

officers. Most counties have an active branch of the Campaign to

Protect Rural

England (http://www.cpre.org.uk).

Many communities have a green-minded

local Friends of the Earth group (http://www.foe.co.uk).

Some have a

group of British Trust for Conservation Volunteers (BTCV), or a

BTCF-affiliated organization (http://www.btcv.org).

Groups like this

may or may not be able to help you with a river project, but they will

usually be receptive and sympathetic, and they can also be a source of

willing volunteers for your own project.

- The editor of your local paper. He

or she may well turn out to be one of your biggest allies. Several

local papers have championed community-based river cleanups in recent

years.

The

other people you need to contact are the riparian owners—the

people who, in theory, own your river. But first you need to find out

who those people are. You could try the Land Registry. You could walk

along the river asking at houses and farms on the route. Or you could

ask your local Environment Agency to help you.

Once

you've contacted all these groups, why not set up a meeting between

all the interested parties? Outline the problem and see what

solutions you come up with. Float the idea of setting up a community

river group. If people are receptive to that idea, you could form an

alliance between these groups where each contributes, in some small

way, to getting the project off the ground. If they are not

receptive, and your idea is still a good one, you may need to go it

alone.

Either

way, all this talking can take a long time and it can rapidly dampen

your enthusiasm. There's nothing worse than being seized by the

determination to start a river project... only to get bogged down in

months of bureaucracy with four levels of local government. You could

save your letter-writing for those long, dull winter evenings when

getting out is harder than you'd like it to be. Another way to cut

through red tape is to set deadlines. Announce that you're going to

hold a local river jubilee on a set date in six months time and see

how much faster the local groups move! But remember that some groups

meet only very infrequently. Parish councils, for example, often meet

only once a quarter—so don't expect them to give you their

blessing by return of post.

5.

Finding out about rivers... and your river

Okay,

so you've decided to set up a river group or campaign. But what do

you actually know about your river or about rivers in general?

Chances are, you are an ordinary member of the community who just

happens to care about rivers—not someone with a Ph.D. in the

spawning cycle of the Atlantic salmon! So it's important to do some

research. Find out as much as you can about rivers in general and

your river in particular.

There

are lots of good introductory books about rivers. One of the best is The

New Rivers and Wildlife Handbook,

published jointly by RSPB, the National Rivers Authority, and The

Wildlife Trusts. It's a comprehensive practical handbook and guidebook that explains exactly

how rivers work and it's available from RSPB (http://www.rspb.org.uk/).

You

also need to find out as much as you can about your local river.

Someone at the Environment Agency should be able to help you find

things like catchment plans and management plans—the official

documents they produce to explain how rivers will be managed in

future. You should also look at things like the Local Plan for your

district and your county Structure Plan, the documents that set out

how your area will change and develop over the next few years.

6. Go

round in circles!

Setting

up a community river group is never a neat and easy thing; you're

bound to go round in circles from time to time. Sometimes this is a

really good thing! For example, if you started out with the idea that

you were going to set up a river-cleaning project, then did all the

research and contacted a variety of interest groups, you might decide

to revise your initial objective: you might decide that it's better

to join forces with an existing environmental group, for example, or

you might find that cleaning up the river really involves mounting a

campaign against disaffected teenagers—and building them a

skate park on the other side of town. Once you've done your research

and contacted local groups, revisit your original objectives. Are

they still valid? How have your ideas changed? Setting up a community

group is an iterative process—and going round in circles is

definitely a good thing (at least some of the time).

7.

How will you organize your project?

Community

river projects vary enormously in size and scope. At one end of the

scale, there are initiatives like the Mersey Basin Campaign (http://www.merseybasin.org.uk/),

a

25-year project with millions of pounds of government money to spend

on urban regeneration centered on the Mersey communities. More

commonly, there are dozens of tiny river groups set up as charities

that carry out all kinds of restoration projects on their local

rivers. At the opposite end of the scale, there are individuals who

just walk along river banks picking up litter. All of these are

perfectly valid approaches to a local river project.

To

start off with, you could just run your group as a loose collective.

Meet in your house or (better still) in the local pub. Decide what

you want to do among yourselves—and then just go out and do it.

If you want to be more formal, elect a chairperson, secretary, and

treasurer, adopt a written constitution, and set up a bank account

for your funds. More formally still, look into setting up a

registered charity (see the Charity Commission website http://www.charity-commission.gov.uk),

but

bear in mind that this takes time (usually up to a couple of years),

costs money, and requires a certain amount of ongoing bureaucracy

(such as the need to operate within very carefully stated aims and

the legal requirement to file annual accounts).

8.

Finding like-minded people

You

can get this far all by yourself, if you want to. But to get much

further, you really need to involve other people. Community

activities, by definition, are social activities.

Getting

other people involved greatly multiplies the effect you can have, if

you do it right. It not only gives you more opportunity to make a

difference, it turns your community project into a fun social

activity and a great new way to meet like-minded people.

Having

said that, finding people to help you can sometimes be a challenge.

You will have found some allies already by contacting the

organizations mentioned above. An appeal through the local media is

another obvious step. Contact local papers, radio stations, and TV

stations and see if they'll run a story about your project. If you're

planning an event, such as a major river cleanup, the media will

almost always give you some sort of advanced coverage. Ideally, give

them at least a week's warning so they can plan ahead and, if they

promise to run a story, phone them a couple of days beforehand to

check that they haven't forgotten.

9. So

what will you actually do?

By

this stage, you should have a pretty good idea just what you're

doing. It might be a river cleanup, a river restoration project, a

campaign to save a threatened river or stop pollution, or a campaign

to have a waterway turned into a safe swimming area with proper

information boards, life-belts, and so on. Any of these projects

could involve any number of different, ongoing activities. A river

cleanup could tackle different parts of a polluted river bank one day

each month, for example. Or a campaign for safe swimming could

involve a safe-swimming day when you arrange for strong-swimmers to

act as marshalls to prove that a particular area really is safe.

Generally speaking, it's best to have an idea how your project or

campaign will play out over a period of time: don't just think up a

one-off activity, but try to imagine how things will develop over a

period of months or years.

Don't forget: you're not the first or the only river group in

the UK. There's a lot you can learn from all the other groups that are

already running, both in the UK and overseas. Some have websites

describing their activities that will give you great ideas. Take a look

at our Network page (https://www.ukrivers.net/network.html)

for contact details.

10.

River cleanups

The

simplest way to adopt a river is to take a dirty one... and clean it

up! First, you need to know exactly what's wrong with the river. Does

it run through a town park where people toss in their litter? Does it

run down from a factory or farm where pollution levels are too high?

Is someone abstracting too much water (taking out too much)? Or is

the problem a combination of all these things? There's no point

trying to clean up a river until you've found out exactly what's

wrong with it, so make that your first priority. Contact your local

Environment Agency office and ask to speak to someone about it.

Discuss what action they are taking and see whether they think a

community group could help.

British Trust for

Conservation Volunteers (BTCV) publishes lots of useful information

about practical conservation work, including information about wetland

restoration. The BTCV Practical

Conservation Online website

is a great place to start.

Is it

safe?

It's

easy to organize a community river cleanup and you'll be

surprised—even amazed and delighted—how ready some people

will be willing to help. But there are significant dangers and

pitfalls. Rivers and inland waters can obviously be very dangerous

places, so you need to investigate very carefully the risks of doing

a cleanup before you start. Is the water deep? Is it choked with

weeds? Is there deep mud or silt? Is it actually safe for anyone to

go into the river to clean it, or should you just stick to the banks?

If you plan to organize a local

river cleanup, you (or your river group) might want to take out public

liability insurance to cover you in the event someone has an accident.

Insurance isn't necessarily that expensive. British Trust for

Conservation Volunteers (BTCV) offers insurance

of this kind to

conservation groups. A local insurance broker might also be able to

help.

What

equipment do you need?

It's a

good idea to make a preliminary survey of the river before you try to

clean it up. What sorts of rubbish are you likely to have to remove?

How will you do that? You'll need obvious things like lots of bin

bags (including black bags for rubbish and other bags for recyclable

items). But what will you do with abandoned shopping trolleys and

larger items? Or broken bottles, syringes, and other sharp and

dangerous objects. Think ahead, plan ahead, and make sure you're

prepared.

It

might help to have at least one person on hand with a pair of waders

or someone wearing a wetsuit (plus wetsuit gloves and surfing boots

if the water is especially cold). A small rowing boat might also be a

good idea.

Beaches

and coasts

River

cleanups help to keep our seas clean too: if we can keep some of the

rubbish out of our rivers, we can help to reduce marine pollution.

The Marine Conservation Society (http://www.mcsuk.org)

has a

long-running Adopt-a-Beach scheme (http://www.mcsuk.org/beachwatch/)

that you could help out with if you do not live near a river. Apart

from shifting mountains of rubbish, the MCS collects data about beach

pollution as part of a long-term strategy to draw public attention to

the problem. The MCS is also interested in working with river groups

to study how river pollution contributes to coastal pollution. So if

that interests you, get in touch with them.

11.

River restorations

If

your river is suffering from neglect or bad management, cleaning up

is less the order of the day than restoration. This is a much more

specialized job and it does require greater knowledge of what rivers

are about, how they work, and how people can help them along. If

you're thinking of river restoration work, you will need help (or at

least guidance) from real river experts, especially if your river is

of high ecological value. If your river is designated as a SSSI or

contains protected species, you must seek expert advice. The best

places to start will probably be your local Environment Agency

office, English Nature team, or Wildlife Trust. We've listed some

other contacts in the back of this brochure. Take a look at the

section on river restoration in The New Rivers

and Wildlife

Handbook. Also check out the

excellent River Restoration Manual

published by the UK's River Restoration Centre. It's available online

and in paper form (at http://www.therrc.co.uk/manual.php).

As we mentioned above, British Trust for

Conservation Volunteers (BTCV) also publishes lots of useful

information

about practical conservation work, including wetland

restoration. See the BTCV Practical

Conservation Online website; in particular, take a look at their

Waterways and Wetlands guide)

If

your river is suffering from neglect or bad management, cleaning up

is less the order of the day than restoration. This is a much more

specialized job and it does require greater knowledge of what rivers

are about, how they work, and how people can help them along. If

you're thinking of river restoration work, you will need help (or at

least guidance) from real river experts, especially if your river is

of high ecological value. If your river is designated as a SSSI or

contains protected species, you must seek expert advice. The best

places to start will probably be your local Environment Agency

office, English Nature team, or Wildlife Trust. We've listed some

other contacts in the back of this brochure. Take a look at the

section on river restoration in The New Rivers

and Wildlife

Handbook. Also check out the

excellent River Restoration Manual

published by the UK's River Restoration Centre. It's available online

and in paper form (at http://www.therrc.co.uk/manual.php).

As we mentioned above, British Trust for

Conservation Volunteers (BTCV) also publishes lots of useful

information

about practical conservation work, including wetland

restoration. See the BTCV Practical

Conservation Online website; in particular, take a look at their

Waterways and Wetlands guide)

12.

River celebrations

Maybe

your river is in perfect condition—lucky you!—and you

want to make sure it stays that way. One way you can achieve this is

to help your local community appreciate the river more. Why not

organize a river celebration or fete? It can be as low-key or as

ambitious as you like.

You

could arrange it for a hot summer's day, or you could make it a

regular fixture throughout the year. You could time it to coincide

with World Water Day (held each year on 22 March; see http://www.worldwaterday.org/),

World

Environment Day (around 5 June each year; see http://www.unep.org/wed/), or the

International

Rivers Network's Day of Action Against Dams and for Rivers, Water, and

Life (14

March each year; see http://www.irn.org/dayofaction/).

Tie in with one of these events and you can use

your celebration to make a bigger point: water is a valuable but

dwindling resource for people throughout the world. You could also

use a celebration as a fundraiser either for your own group or for a

group like WaterAid, a London-based charity that helps to bring clean

water and sanitation to less fortunate people in developing countries

(see http://www.wateraid.org.uk).

Organizing

a river celebration sounds hard work—but it can be incredibly

easy. What about organizing a walk down the banks of your local river

one summer's evening? Invite a local wildlife expert to come along

and give a commentary. Publicize the event in your local paper and

get them to come along and take some photos. Maybe hold a picnic at

the start or the end of the walk, or arrange the route so you start

and end at riverside pubs.

Is

this really adopting a river?

Of course! By helping people to recognize and appreciate the value of

rivers, we give people reasons to look after them.

13. River recreation

Maybe

you like swimming in your river, if it's safe to do so. Or maybe

you'd like to make your river safe for other people to swim in.

What's the best way to go about it? Many of our rivers and inland

waters are perfectly safe for swimming in. The problem is that there

is a lack of good information telling people where it is safe for

them to swim. The fault lies with our governments, national as well

as local. Under European law (the Bathing Water Directive),

governments have a legal responsibility to identify where people

bathe regularly and then to designate those areas as official bathing

waters, with appropriate signs, information, and other facilities.

Most bathing waters in the UK are, unsurprisingly, at beaches and

coastal areas. Elsewhere in Europe, there are many more designated

bathing waters inland. So if you have a place where people bathe

regularly, why not mount a campaign to have it officially designated?

You may need legal and other help—which the UK Rivers Network

will be pleased to advise you on further. The River and Lake Swimming

Association's website (http://www.river-swimming.co.uk)

is a great

place to start to find out more about swimming in inland waters.

14.

River campaigns

Thankfully,

a great deal of the damage that people do to rivers is reversible. We

can pick up litter, we can restore river banks, and we can attempt to

reintroduce valuable species such as otters and water voles. Other

kinds of river damage are harder to tackle. Housing estates built on

floodplains, motorways that pollute rivers with toxic runoff,

quarries that destroy wetlands, and landfills that leach toxic

pollutants over decades and centuries all pose a grave threat.

Sometimes adopting a river means setting up quite a confrontational

environmental campaign to fight a development head on.

Environmental

campaigning is a huge topic and we don't really have room to explain

all the ins and outs here. Essentially, the objective is to mobilize

massive public opposition to a development and then target the full

force of that opposition at decision-makers in either national,

regional, or local government. That sounds easy; in practice, it can

take many months or even years, it can sometimes cost a great deal of

money, and it can cause permanent rifts in a local community. But it

can also be incredibly worthwhile and rewarding and, when it works

out, it can help to safeguard parts of our priceless environment in

perpetuity.

Campaigning for rivers illustrates the more challenging side of

cooperation and

confrontation. In a perfect world, we would all get on fine,

cooperate entirely, and spend all our happy summer evenings going for

pleasant walks by the river. In our imperfect, highly compromised

world, we're more likely to spend the evening pulling shopping

trolleys out of the town pond, writing angry letters to the local

paper, or ranting at a public meeting. Sometimes it is necessary to

be confrontational. Some people enjoy taking on “greedy

developers” or "corrupt councils"; others find the whole thing

distinctly uncomfortable and objectionable.

16.

Enjoy yourself!

Whether

you are planning a campaign to stop a quarry or an annual celebration

of a chalk-stream river, the key to success is to enjoy yourself. Try

to be as effective as you can, but don't forget to enjoy yourself and

have fun!

18.

Tell us how you get on

The

lessons you learn can be of great benefit to other people, so please

do get in touch to tell us how you get on. Maybe sit down and write

us a case study of what your river project or campaign tried to

achieve and how you did it. What pitfalls did you face and how did

you overcome them? What have been your greatest successes.. and your

biggest failures? What advice would you give to others.

Do

please keep in touch!

Case studies

-

My story:

freshening up our river:

Chris Scott hopes to transform the River Freshney in Grimsby from a

rubbish dump to a paradise—and in this story he explains how the BBC

Action Network is helping along the way.

Copyright © UK Rivers Network 2004.

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons License.

Major Badger:

Picture by "V"

Major Badger:

Picture by "V"